The jury is still out on our effect on Kartchner Cavern's mama bats, but we're a big hit with cave slime.

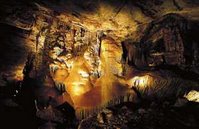

The jury is still out on our effect on Kartchner Cavern's mama bats, but we're a big hit with cave slime.Since humans started visiting in numbers — the cave opened in 1999 — some microscopic cave species are "getting fat and happy," said Raina Maier, a University of Arizona professor of soil, water and environmental science studying the cave's microbes.

Maier heads a UA team recently awarded a five-year, $1.6 million National Science Foundation grant to monitor microbial activity in the caves 50 miles southeast of Tucson.

Although the National Science Foundation-funded portion of the study is just getting under way, Maier said ongoing work at Kartchner shows that the microbes that appear to be thriving aren't directly connected with humans. But, she said, it's likely they're thriving thanks to the nutrients cave visitors leave behind.

Although the National Science Foundation-funded portion of the study is just getting under way, Maier said ongoing work at Kartchner shows that the microbes that appear to be thriving aren't directly connected with humans. But, she said, it's likely they're thriving thanks to the nutrients cave visitors leave behind.She said human visitors inadvertently leave behind skin cells, hair and lint, which can become food for microbes.

In the case of the aforementioned bacterial slime, the manmade dinner is even more disgusting than skin, hair and lint. Maier said what got researchers' attention in the first place was "a copious slime" living and dining on paint that had been applied to Fiberglass housings concealing electrical and plumbing systems.

But in parts of the cave far off the human path, it's apparently still slim picking for microbes. Nearer the human pathways, the microbes are living higher on the hog, though it could not be called "nutrient rich," said Maier.

But in parts of the cave far off the human path, it's apparently still slim picking for microbes. Nearer the human pathways, the microbes are living higher on the hog, though it could not be called "nutrient rich," said Maier.Oddly enough, though microbes near the human paths appear to be thriving, there are fewer species of microbes close to pathways (22 to date) than in areas more removed from humans (32 species, so far), said Maier. " (...)

Read the full article: Aazstarnet.com

No comments:

Post a Comment